On the Verge of a New World

Words

Arielle Bier

Interview

Hans Ulrich Orbrist

Formafantasma

Story from Issue 15

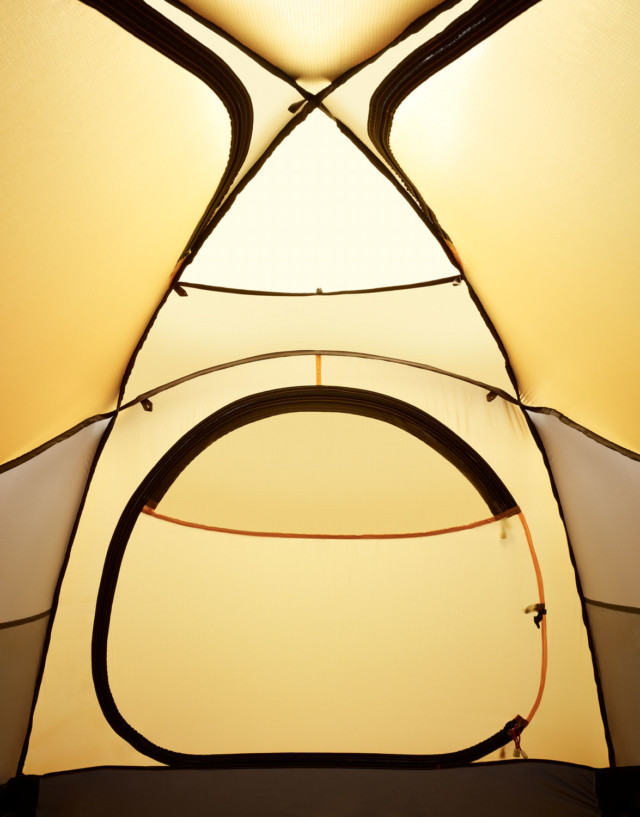

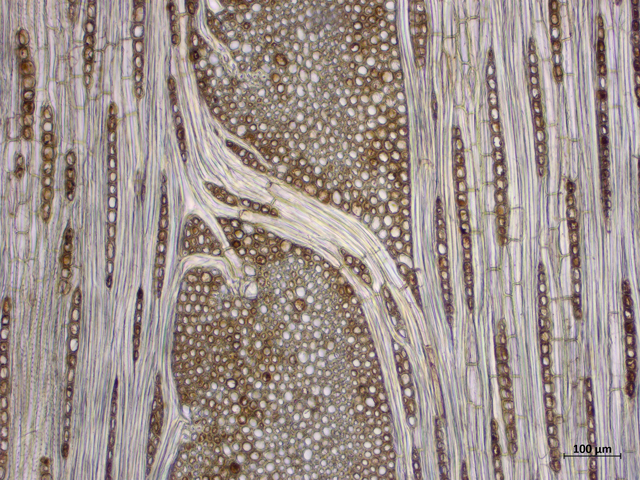

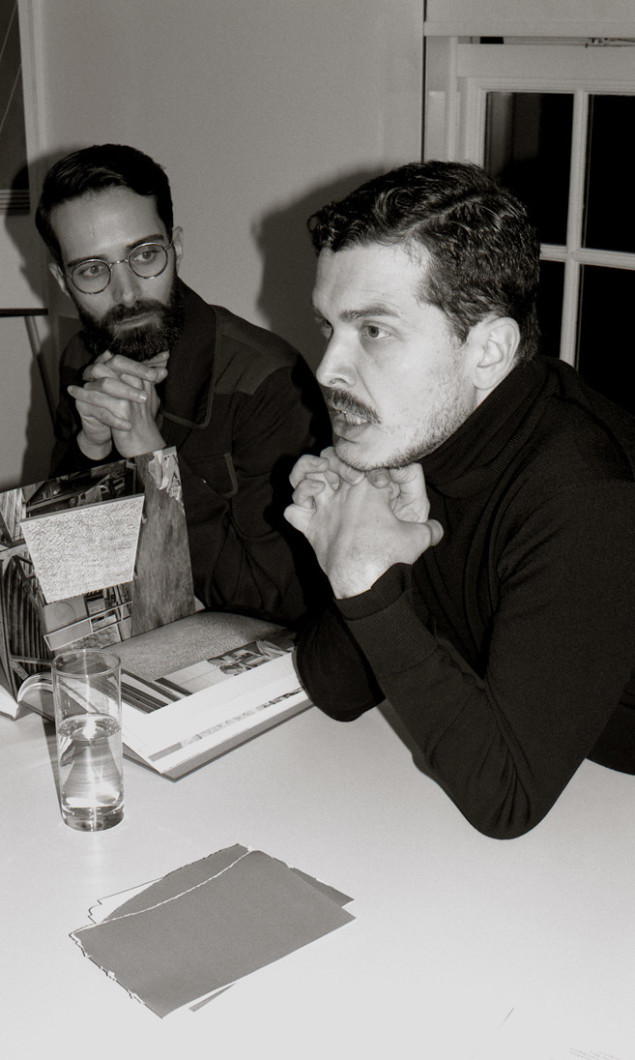

On the verge of their exhibition opening, Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin of Studio Formafantasma met with Artistic Director of the Serpentine Galleries, Hans Ulrich Obrist, to discuss their project, Cambio. For over a year, the Italian designer duo investigated one of the most widely-used living materials: timber. Tracking how the wood is sourced and used, they turned their insights into a design-led exhibition, examining the material from its scientific structure to met a physical essence. Using craft to discuss how materials are transported around the globe and end up in the lives of users, Formafantasma spotlight the historical, political and social forces at play and the implications of turning natural resources into commodities. Timely themes surrounding climate, ecological and economic crises arise throughout the interview, yet no one could have imagined the uncanny parallels that the Covid-19 pandemic, which promptly closed the galleries to the public, would emphasise about the need for conscious living.

HANS ULRICH OBRIST We felt it’s very important to kick off the Serpentine’s 50th anniversary year with a design exhibition. Every year or two, we invite a designer todo a show. It began with Konstantin Grcic, who curated a show of mass-produced objects. He looked at the history of these objects, their production facilities and the way they’re produced. Each object he chose had its own history and timeline. Then we ran another exhibition with Martino Gamper, who wanted to design an archive—it was a landscape of shelving systems, telling the story of design objects and their impact on our lives. That show was like a Russian matryoshka. And now, for the third time, we’ve invited Formafantasma. And we must, of course, thank Alice Rawsthorn—the great design guru who has the best Instagram on all of planet Earth. For everybody who reads this: Follow Alice Rawsthorn on Instagram! For us, working across disciplines is central to everything we do and we will continue to host more design shows in the future.

Now, it’s interesting because this show deals with ecology, which has played a big role for us for over ten years because of Gustav Metzger. I want to remember Gustav Metzger, our friend, who came here every week and re-minded us that we need to fight extinction. He called on the art world to use their agency, to get people to wake up to the threat of our planet’s destruction. He always said that we cannot only talk about climate change because people will never wake up. We need to talk about the reality, the extinction of species. And your exhibition deals with this topic—not only the extinction of species but also of diversity, cultural phenomena and homogenisation.

Metzger addressed this with his exhibitions. He came into the office the day after his opening and said, “Don’t believe it’s done. We need to continue.” Then we did the Extinction Marathon. Again, the morning after the Extinction Marathon, he stood in my office and said, “Don’t believe it’s done. This topic is going to be an important topic for the rest of our lives.” A week before he passed away, he asked me to come to his apartment for a farewell visit. He held my hand and said, “You have to promise to continue the fight.” So, in a way, we continue what Gustav told us to do and I think he was so right. He was a mentor of our awareness, of the necessity to fight extinction.

Last time, I asked you how you came to design but today I want to ask the question differently. Who is your Gustav Metzger? Who is your mentor? How did your awareness start?

SIMONE FARRESIN For Andrea and I, it’s not only about the work but the life we live. Our awareness came from the mission itself, as a form of refusal. Seeing the market develop in such a way that is destroying the planet, we felt that we had to react. We saw a lack of responsibility, which drew us to a much clearer understanding of the dangers we are facing at this moment. After the Second World War, the global markets developed as a response to what was happening: the need for reconstruction. In this moment, design needs to think beyond humans. For centuries, design has only fulfilled the needs and desires of humans. Our interest in ecology developed from this reflection, from the responsibilities of the discipline. Then we also began reading things, watching documentaries and simply leading our lives. And we started really feeling like something is going wrong in the world. It also came from our surroundings. My father is a farmer. He’s been telling me how his perception of the world is changing, that even the forests where he grew up aren’t there as he remembered.

ANDREA TRIMARCHI Being a designer, it’s more difficult to have a model to follow. Very few people are thinking about the environmental crisis. In art, you can find many more writers or other people dealing with the Anthropocene but in design there isn’t as big of a discussion about it.

SIMONE Donna Haraway is somebody that helped us grow towards this sentiment. I’d first read A Cyborg Manifesto when I was sixteen or seventeen.

HANS Let’s talk about your beginnings with ecology and Botanica. What brought about this project?

ANDREA Botanica addresses many ecological issues. It was a commission from Fondazione Plart in Italy, dedicated to the restoration of objects made in plastic. Plastic is the material of the contemporary, it’s one of the most demonised materials in the world. And they commissioned us to make a project around plastic.

SIMONE Which we hated, of course. We really wondered why they called us to make an exhibition about plastic? But then we started looking into the design history and rediscovered materials that were used before oil was processed into plastic. The first polymers were either animal or plant derivatives and we reconstructed these materials, collaborating with scientists and material restorers. Some of these materials, like natural shellac, are made from insects that live in the trees in East Asia. Or bois durci, for instance, is a mixture of animal blood and wood fibre. Through understanding the historical development of plastic, we attempted to prove that often there are things we leave behind in the past, which can be relevant for the future.

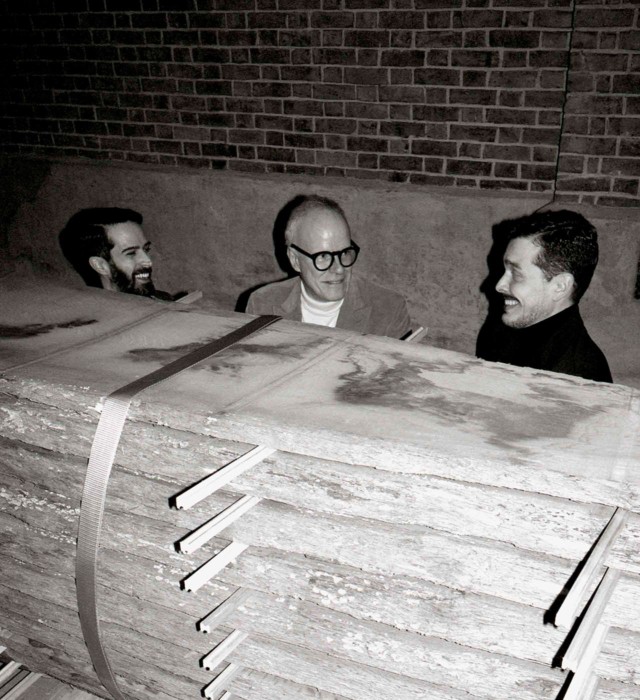

HANS I’m interested in these objects you’ve reinvented from the past, like the works of Enzo Mari who you’ve mentioned as one of your inspirations. I’m curating a retrospective of his work for the Triennale in Milan, or which you contributed a catalogue text. For me, he’s always been one of the great designers of the second part of the 20th century. The amazing thing about Enzo Mari’s work is that it’s the opposite of disposable design. It ages so well. His designs aren’t obsolete or dated. It’s fresh.

ANDREA We love Enzo Mari for many reasons, but one of the things we are most proud of is the way he built very strong relationships with the companies he worked with.They really allowed him to explore ideas in a much more profound way. Nowadays, this is very difficult to do in contemporary design. He also had a profound interest in human beings and respect for the labourer. Though, I think he wasn’t so into nature.

SIMONE Or ecology. But in a way, it’s also not needed for him to be such an influence. Another reason we love his work is because he went beyond what most people considered to be design. When he looked into a project, it was never just about the form, the colours and the materials. It was also about the labourer, the production, the under-standing of the ecology of design. He was very political.We loved his statements and the way he was so unapologetic. Thinking of Enzo Mari’s work is a reminder of good design, it makes you think of what’s relevant.

HANS And what was your project about Enzo Mari like?

SIMONE It was called Autarchy.

ANDREA And it was first shown in 2009, in the middle of the economic crisis. We were exhibiting during the Salone del Mobile in a small gallery, in the basement.There were many shiny exhibitions that year. The atmosphere was very decadent.

SIMONE We used biodegradable materials like flour to make very humble vessels. We also worked with a broom-maker to make straw brooms and a baker, who brought this love of bread with him. I think what he liked the most was that we were actually making the vessels ourselves. We had a vision of a utopian scenario, of a rural community who are growing one cereal, who are feeding themselves and also producing objects out of it. In a way, it’s a simplified version of an entire economy.

HANS When I first got to know your work, it was about phones. You’ve been very concerned about what’s happening to these devices, which usually end up in slums, mostly in Africa where they are being dismantled and causing toxic waste. How did this idea start and what’s your vision of recycling these phones?

SIMONE We were doing this project called Ore Streams for a museum in Australia, The National Gallery of Victoria. Australia is such a large extractor of underground minerals and we wanted to address this but link it to contemporary times. We know that in about eighty years, the majority of minerals we use will come from recycled sources. When we talk about recycling, we all think it’s great. Nevertheless, we wanted to be critical and really look into it. The fact is that electronic waste is increasing all over the world and the project became about proposing pragmatic strategies for making electronic parts more repairable and recyclable. We also held conversations with policy makers, ngos developing responsible workshops in India and Kenya and other practitioners.

ANDREA We made several videos addressing how design can have an impact in making electronic products more durable and addressing planned obsolescence. Basically a lot of the products we buy are designed with components that have expiry dates. This is something that absolutely must change if we want to make these products more ecological.

SIMONE As designers, our aim is to intervene at different levels, meaning that there are different scales that design can operate in. We don’t think recycling products is enough, but the complex systems in place require different scales of intervention. This is something we are planning to apply to our master’s programme that starts in September, called Geo-Design. We’ll offer this opportunity to students, for ad-dressing different issues from different perspectives. These solutions might take the form of extraordinary philosophical reforms or finding different ways of changing policy, or more traditionally work at the level of product design.

HANS That’s a great end of chapter one. Now, for chapter two. I would like to discuss the Cambio project. Your exhibition addresses the Anthropocene, climate emergency, ecological diversity, and the idea that homogenised globalisation makes diversity disappear. You researched this project for over a year. Can you speak about the genesis and slow programming of Cambio?

ANDREA We started the project a year and a half a go and we decided to take time for this one. Usually, we do projects more quickly. To go more deeply into this project, we needed more time. At the beginning, we started investigating different types of materials and then we concentrated on one material that’s most used worldwide: timber. It’s also a living material.

SIMONE Initially, we wanted to find something that any-body could engage with. We became extremely fascinated with timber. It allowed us to address issues, like the intelligence of non-humans, in this case trees and the ways we produce objects with these living species. The exhibition starts with a very pragmatic perspective and ends with apolitical view on the subject. For example, one video has a voice-over where a tree speaks back to humans. The video asks for the reconsideration of our position on the planet and if humans are really the dominant species or if the entanglements on Planet Earth are way more complex. I’m sure many designers would find this esoteric, but in fact, we believe it’s important to put these questions forward and really ask what we’re doing on the planet. Designers must look beyond the fulfilment of human desires.

HANS How do you expect visitors to react? Some may take it as a call to action.

ANDREA There is a part of the exhibition that’s very didactic. One video explains the historical development of the timber industry, another looks at its contemporary governance and the impact of illegal logging in the market. These are massive issues that very few people are aware of. We’re so used to going to IKEA and other shops to buy things we need. We don’t think so much about the means of extraction of these materials from nature. From the exhibition, I think people will gain a different idea of wood and trees, and hopefully understand the ecological implications of design and production.

SIMONE Imagining the impact of the work is very difficult and we hope great things for any work we do. We know that we won’t change the industry with this volume of work. In this respect, we want to take this body of work and make it part of the curriculum of our Geo-Design programme in Eindhoven, so it can grow with the next generation of designers.

ANDREA Or with companies.

SIMONE We have been talking for months with several companies about integrating some of the ideas of the exhibition on their production lines. So, we hope that can become a reality.

HANS Can you tell us about how you translated your research into the exhibition context? How does one translate research, to display, to exhibitions and also to design objects?

SIMONE We tried to balance the part that can be more didactic with the parts that are more emotional or poetic. We wanted to work at a meta-level. It was also important for us that the making of the exhibition itself made sense for the show. One of the things we decided to do was limit the temporary interventions in the space, as much as possible, and leave the walls as naked as they are. We avoided having clichéd, white cube exhibition supports. Instead, all of the supports we’re using, like the tables and shelves, are designed to have a life after the exhibition. We had the exhibition displays of Carlo Scarpa, Lina Bo Bardi and other of our favourite designers in mind. Their exhibition designs was so durable and convincing that they managed to out-live the exhibitions they were conceived for. The wood that we use is sourced from a forest in northern Italy, which had been destroyed by a storm caused by climate change about a year ago. In just one night, 14 million trees were destroyed.It caused an emergency there. The trees must be removed from the forest immediately because if they rotted they would have contaminated the rest of the environment and they also would have released an incredible amount of CO2.

HANS So you removed the trees.

SIMONE Not 14 million, but one. Of course, it’s much more about the symbolic gesture. We wanted to think about the exhibition display as a way to address this. Again, it’s a small thing but we tried to do that. To show how design can make more informed choices.

HANS That leads us to the last question. We know a great deal about architects’ unrealised projects because they publish them, but we actually know very little about the unpublished projects of designers, artists and poets. Can you speak about one unrealised Formafantasma project? A dream? A utopia?

SIMONE There’s one unrealised project, a very pragmatic one. I personally would really love to do a project about public water in cities. Or, another project we would love todo is to design a garden.

ANDREA The garden is the only one we talk about all the time.

HANS How would your garden be?

ANDREA We think about trying to gather all of the resources needed to make an object like the iPhone. They require materials that are extracted from all over the world, from Africa, from South American and from Asia. We see it like a Pangea of different worlds colliding.

SIMONE We would like to see what the iPhone environment looks like—not thinking about it as a product but as a group of resources. What kind of landscape would that be? What kind of planet would it be? It would encompass plants, animals and minerals.

HANS Even the garden will be based on the iPhone garden.

SIMONE Maybe it doesn’t need to be executed, but we would like to understand, to experience that planet, that garden.

HANS That couldn’t be a better conclusion. §